Rescued Work: Michael Jackson & Hip-Hop

DEF|Y|NE Media founder Matthew Allen revisits an erased 2017 article that connected Michael Jackson to all five elements of Hip-Hop throughout his career.

An important edict of DEF|Y|NE Media is to add to the conversation; to find new and alternative angles for topics and people that publications and outlets always cover. Michael Jackson was a man who was chronicled so severely, finding new things about him to talk about proves to be a challenge that most people don’t even attempt.

As a music journalist, I embrace the challenge of finding undiscovered angles on popular subjects to uncover. As a Michael Jackson fan, the task is easy because outlets love to repeat themselves when it comes to him. During my time at Mass Appeal, one of the more important hip-hop magazines, I got to pitch a feature that connected the dots between MJ and hip-hop.

Originally titled, The Five Elements of Michael Jackson: How The King of Pop was the Quintessential Hip-Hop Superstar, I broke down all the ways that Jackson utilized the five elements of Hip-Hop in his artistry. In 2021, I used excerpts of this article as a script for my first video essay of the same name.

The year was 1986. Quincy Jones had contacted Run-DMC to come to record an anti-drug song with none other than Michael Jackson, the enigmatic megastar singer/songwriter, who passed away eight years ago today. After the Rap trio stepped on a white sequin glove in their 1984 video “King of Rock,” one would think this would be a tense meeting of artists. The feeling was mutual. According to Jones, MJ stated to him that “rap is dead.” Although by all accounts, their interaction was cordial (the song failed to make the Bad album), the singer’s statement proved ironic.

When you put Michael Jackson under the microscope, he is an archetypal Hip-Hop artist. With the hyper-masculine subtext surrounding the culture juxtaposed to the soft-spoken, child-like, androgynous personality of Jackson, it’s easy to overlook that the guy embodied all that hip-hop has to offer.

For Hip-Hop artists, it starts with the come-up; that rags-to-riches grind that rappers and producers go through to get put on by a crew and/or a label. Jackson’s come-up came through Gary, Indiana. He and his brothers performed at seedy bars and strip clubs as minors in the bleak steel town before getting Berry Gordy to sign them to Motown in 1968. MJ’s ambition to be a star can be likened to the killer instinct of 2Pac, LL Cool J, and especially Kanye West.

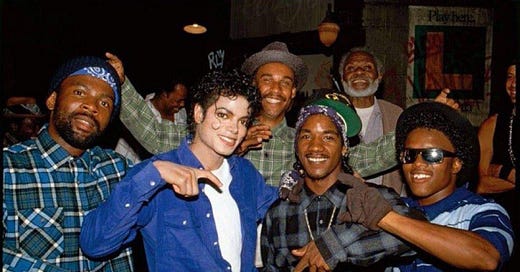

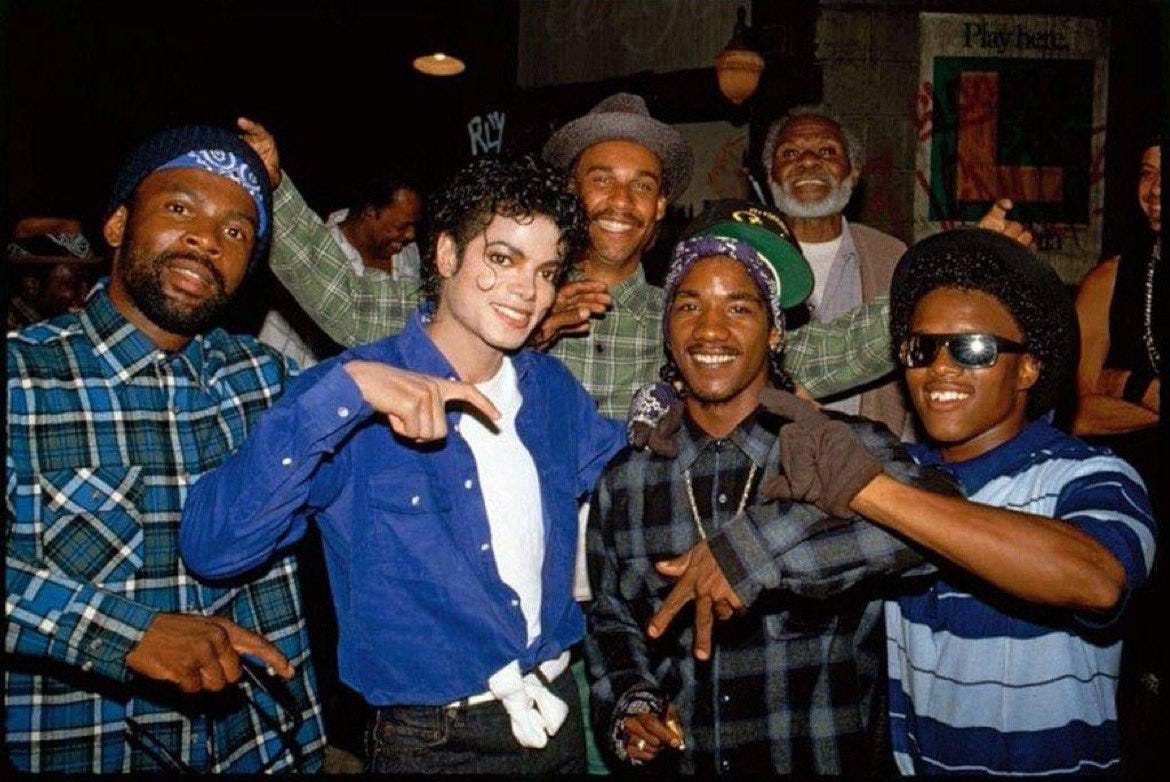

Wanna talk about street cred? Decades before Chris Brown wore red bandannas on stage and was throwing up hand signs in club V.I.P. sections, Jackson enlisted real-life street gangs for his music videos. He aimed to achieve an authentic grit and grime for the viewer, and he did it before EVERYONE. He put members of the Los Angeles Bloods in the 1983 “Beat It” short film, wearing that iconic red zipper jacket. He had members of the Crips in 1987’s “The Way You Make Me Feel” short film, and wore a blue button up. Coincidence? Maybe, maybe not.

Whenever Jackson aligned himself with Hip-Hop practitioners, he made sure to do it with the best. From enlisting Heavy D on “Jam” for 1991’s Dangerous album, having Notorious B.I.G. drop a rapid fire 16 of paranoia in 1995 on HIStory’s “This Time Around,” to pleasantly surprising fans at Hot 97’s 2001 Summer Jam with Jay-Z (leading to him singing background vocals on Hov’s “Girls, Girls, Girls” remix), Jackson as much as anyone proved game recognizes game. His main post-Quincy Jones producers, Teddy Riley and Rodney “Darkchild” Jerkins, were perfect fits for his futurist musical mind. Jackson was consumed by rhythm from day one, the essence that shoots through the veins of Hip-Hop’s music culture.

The Hip-Hop artist’s story is often fraught with narratives of being the underdog, being overlooked, and overcoming haters and doubters. Jackson’s achievements and drive were born not only out of his God given talent, but with ambition ignited by naysayers at every turn throughout his life. We often hear DJ Khaled say things like, “‘They’ don’t wanna see me win.” Well, here are some of the things “they” thought about Jackson:

The Jacksons will never get out of Gary.

The Jackson 5 will never have a hit record.

The Jackson 5 will never write their own music.

The Jackson 5 is nothing without Motown.

Michael is nothing with his brothers.

Michael can never top Off The Wall.

Michael can never top Thriller.

Michael has alienated his Black audience.

Michael will never have another number one record.

Jackson continued to win because no matter how popular he became, he retained what makes many rappers great: a chip on his shoulder. If you still don’t make the connection, here’s how Michael Jackson embodies the five elements of Hip-Hop:

B-Boy/Breakdancing

Bottom line, Jackson was arguably the best dancer this globe has ever seen. The virtuosity and charisma with which he moved on stage and in short films are unmatched. The essence of his movement is rooted in Hip-Hop, dating back to before the term was even invented. His influences drew just as much from the Rock Steady Crew as they did from James Brown and Fred Astaire.

MJ always appreciated contemporary street movement. When he broke out the Robot during The Jackson 5’s performance of “Dancing Machine” on Soul Train, it was clear he was paying attention to the Soul Train dancers every week. His mastery of ticking and pop-locking demonstrated from The Jacksons’ short lived variety show in 1977 all the way to his HIStory concerts, came from tutelage from The New York City Breakers and Shalamar’s Jeffrey Daniel.

It was Daniel who taught Jackson a breakdance move called the Back Slide in 1980. When MJ unleashed it before an unsuspecting crowd at Motown 25 three years later, it was forever dubbed the Moonwalk. But for those in the streets who knew better, they felt vindicated and celebrated by the world’s biggest superstar. In 1995, during a performance of “Dangerous” at the MTV Video Music Awards, Jackson broke out a Bank Head Bounce, once again letting us know Neverland ain’t as far from the hood as you might think.

Graffiti-Writing

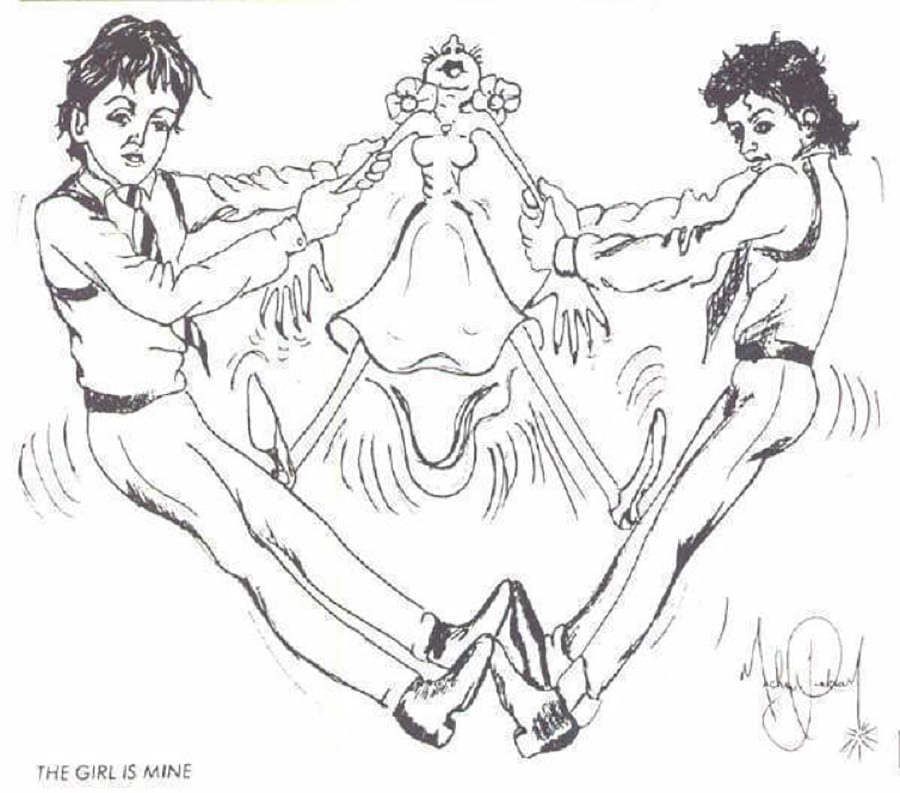

No, Jackson never was out in the streets of Gary, tagging up his pop’s steel mill or Roosevelt High School. However, he was quite the illustrator. Since his Motown days, MJ was notorious for doodling and drawing pictures. Turns out it was a bit more than just doodles. When you see his self-portraits and drawings of Charlie Chaplin or Liz Taylor, Jackson’s talent for illustration was pretty tight; a revelation of his many talents beyond music. Just look at the liner notes of Thriller.

Each side of the lyric sleeve had an illustrated depiction of a song from the album. Side A featured a drawing of him and Paul McCartney playing tug-of-war with a female on “The Girl Is Mine.” On Side B was his depiction of “Thriller”: a scene of Jackson and his date watching a movie, surrounded by night creatures lurking about them. The details of the faces and hairdos melded with the nuance of a caricature artist lead us to wonder what could have happened if MJ ever got a hold of a few spray cans on that sequin glove of his. After viewing his brooding, articulate 1995 drawing of himself as a child, sitting in a corner holding a mic for the song “Childhood,” there’s no telling what kind of paintings and murals he might’ve been able to conquer.

MCing

If the job of an MC is to move the crowd, as Rakim once said, then Michael Joseph Jackson was the real GOD MC. If you weren’t lucky enough to be at one of his concerts, go to YouTube after this and revel in the uncanny mind and body control he had over his fans. If you didn’t just completely pass out from utter shock, you were crying, jumping, dancing, or all of the above. Gauging MCing from an aural standpoint, you could never mistake Jackson for a rapper, but he had all the attributes that make an A1 spit game.

First, there’s Jackson’s flow. MJ helped revolutionize how R&B and Pop singers ride a beat on a track, and his cadence was as seamless and majestic as Jay-Z, Biggie, or Busta Rhymes. Listen to “Off The Wall,” the rare “Buttercup,” and “Jam,” as examples. He took the James Brown approach to rhythm-driven vocal delivery and enhanced it to sinuous and gorgeous effect. Going back to “Jam” and also “Smooth Criminal,” he predated today’s current style of rhyming, fusing melody and percussive atonal vocals prominently practiced by artists like Ja Rule, Nelly, Drake, and Rihanna.

Then there’s Jackson’s wordplay. Low-key, Mike’s pen game was ill. Catch this rhyme pattern on “Heartbreak Hotel” and his clever use of couplets:

“Someone’s evil to hurt my soul/Every smile’s a trial, caught in beguile to hurt me/Then the man next door had told/He’s been here, in tears, for 15 years/This is scaring me.”

Or see him on his Chuck D, KRS-One tip on “They Don’t Care About Us:”

“Tell me what has become of my rights/Am I invisible ’cause you ignore me?/Your proclamation promised me free li-ber-ty/I’m tired of being a victim of shame/You’re throwing me a class with bad name/I can’t believe this is the land from which I came!”

Lastly, Jackson was never scared to address his, haters on wax. On “Bad,” he declares “and the whole world has to answer right now, just to tell you once again/Who’s Bad?” During “Unbreakable,” he calls out his detractors, “Seems like you know by now, when and how, I get down/And with all that I’ve been through, I’m still around.” He even engaged in an on-wax beef with none other than his own brother, Jermaine Jackson! In 1991, Jermaine dropped “Word to the Badd,” a scathing diss to Mike about him stealing his thunder. Mike responded, subliminally at that, in “Jam:” “I told my brother, don’t you ask me for now favors/I’m conditioned by the system/don’t you talk to me, don’t scream and shout.”

DJing

Now, the closest Jackson may have ever been to a DJ booth was when he was vibing in one at Studio 54 in the late 1970s, observing the patrons. However, he didn’t need two turntables and a mic to be able to personify and relate with the mind of a DJ.

Pioneers like Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash and countless others after them rocked the crowd by isolating the breakdown in a record (i.e., the “Apache” drumbeat or the bridge to “Sex Machine”). Jackson’s most exuberant compositions were driven by a single, repetitive line with minimal chord changes. Tracks like “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough,” “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’,” “Workin’ Day & Night,” “Leave Me Alone,” “Jam,” and “Shake Your Body (Down to the Ground),” all songs with soul penetrating bass lines, scratching rhythm guitars and thumping, complex drums with dense kicks, were tailor made for basement parties and night clubs, and he knew it.

Let’s talk about beatboxing for a moment. It seems crazy, but Jackson very well may have invented beatboxing as we know it today. Don’t believe it? Go to his composition “Blues Away” on The Jacksons’ 1976 self-titled album. Right before the outro, Jackson imitated a drum pattern and revving electric guitar riff that was a template for Doug E. Fresh, Biz Markie, and The Fat Boys’ Buffy. In fact, he beat boxed all of his demos, beat boxed the rhythm tracks years before Timbaland did (See “Can’t Let Her Get Away,” “Tabloid Junkie,” and “Stranger in Moscow“). He gave an undeniable beatboxing exhibition before the world live during “Who Is It” in his 1993 interview with Oprah. Can you imagine Jackson and Slick Rick doing “La-Di-Da-Di” together?

Jackson was also a sample trailblazer. He paid Jazz/Funk saxophonist Manu Dibango to interpolate his Swahili refrain for “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’.” Thirty-Five years later, the world is still singing “Mama Se Mama Sa, Mama Coo Sa!” He and Quincy Jones even sampled a Synclavier II preset for the intro to “Beat It.”

The Knowledge

If nothing else can be said of Michael Jackson, he was a student of the game, bigging up his mentors and educating the young’ns with the real. Don’t be fooled by all the “Heal The World,” “We Are The World,” and “Man in the Mirror” idealism. Sure, Jackson certainly saw the good in humanity and strived for peace, but he was as woke as a 5 Percenter. Jackson’s low-key militant Blackness and esoteric ancestral knowledge were not only evident in his wardrobe and in songs like “Earth Song,” and “They Don’t Care About Us,” but also in his imagery.

Jackson’s treatment for The Jacksons’ “Can You Feel It” short film illustrated a celestial melding of fire and water, signifying the reconciliation of human and divine. “Black or White’s” infamous dance sequence in which MJ transformed from a Black Panther certainly couldn’t have been simply for aesthetic reasons, especially given the sociopolitical messaging of the lyrics and destruction of property during the dance. The magnum opus of Jackson’s knowledge of self came in the form of his 1992 “Remember The Time” short film. With an all-Black cast and Black director (John Singleton), Jackson attempted to negate the century-long rhetoric of whites as Egyptians. He reminded the world what the hard truth was, as if to say, remember the time when we were kings and queens? The real truth is the lighter his skin got from his vitiligo, the Blacker his music got…and Hip-Hop’s core is its Blackness.

THANK YOU FOR READING! If you enjoyed this piece, please subscribe to my page and share the piece on social media. Thanks again, and stay tuned for more!