'Half a Mile From Heaven': Revisiting Stevie Wonder's 1980s Catalog

While Stevie Wonder's imperial era took place in the 1970s, his output in the 1980s deserves a proper reappraisal.

(Stevie Wonder portrait. Illustrated by Quincy Ray. Following him on Instagram @quincyray_)

*This is a re-worked version of a previously released article from the original DEF|Y|NE Media blog page, published May 2021*

If you ask Stevie Wonder fans what his prime was, ten times out of ten, they’ll tell you the 1970s. Who can blame them?

During the 1970s, Wonder released eight albums, had 12 top ten singles on the Billboard Hot 100, and earned 12 of his 25 Grammys, including three consecutive Album of the Year wins. His fabled “classic period” from 1972 - 1976, including albums like Innervisions and Songs in the Key of Life, is unrivaled in the annals of American music history.

Adversely, Wonder’s 1980s output isn’t looked at as favorably. Much of his catalog during the “Me Decade,” including songs like “I Just Called to Say I Love You,” “Part-Time Lover” and his participation in star-curated charity hit singles “We Are The World” and “That’s What Friends Are For,” are dismissed as schmaltzy, over-produced songs not worthy of praise like his earlier material.

Ironically, Wonder saw the success he amassed in the 1970s increase in the 1980s. Despite only dropping four studio albums in that decade, all of them reached platinum certifications. Wonder earned 15 top ten Billboard R&B singles (six reached number one), accumulating 22 Grammy nominations (two wins) and winning an Academy Award for Best Original Song for “I Just Called to Say I Love You.”

Was this a result of him selling out and dumbing down his songwriting to reach a wider audience?

Not actually. Here’s why.

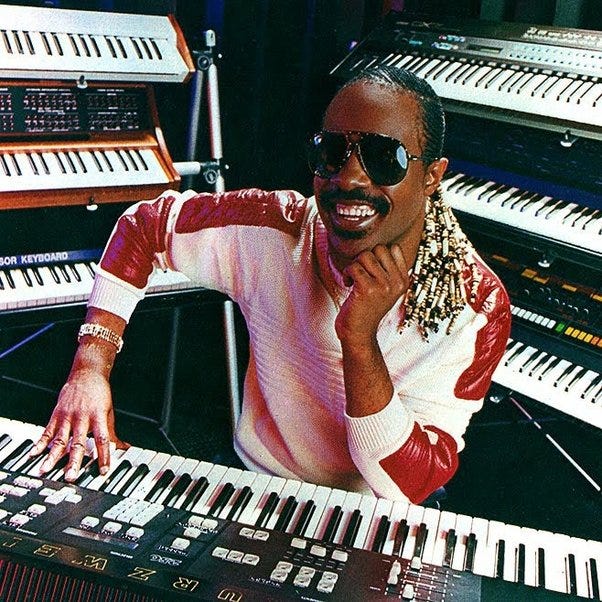

(Back cover of Stevie Wonder’s The Woman in Red motion picture soundtrack album, released in 1984.)

Wonder was a victim of his innovation. He was one of the first Black artists to embrace electronic technology to record his music, after linking with engineers Malcolm Cecil and Robert Margouleff - creators of the massive multi-timbral synthesizer TONTO - in late 1971.

One of the biggest differences between the sound of Wonder’s 1970s catalog from his 1980s catalog was that the latter saw a full-on immersion into digital recording and production, whereas the former featured a more balanced marbleization of electronic and acoustic instrumentation.

Look at a song like “Superstition.” While its main components came from several layers of clavinet, Arp, and Moog synthesizers, live drums, and brass served as a perfect counterpoint.

As the 1970s progressed, artists like George Clinton (“Flashlight”), and Herbie Hancock (“Come Running To Me”) began to follow Wonder’s lead. As that decade closed, synths and drum machines were the rules, not the exception.

The end of the 1970s also proved to be a pivot point for Wonder. For his 1979 album, Journey Through The Secret Life of Plants, he recorded it fully digital for the first time. Wonder used mostly synthesizers, keyboards, and drum machines all but exclusively to record what’s, in essence, a symphonic orchestral film score. Although much of the music itself was pleasant and emotional, the full digital production gave it an undertone of iciness.

Secret Life of Plants, Wonder’s first release following his magnum opus Songs in the Key of Life, received a less-than-welcoming reception, as fans and critics were perplexed and let down. As a result, 1980’s Hotter Than July was hailed as a return to Wonder’s classic form for some. While also another fully digital recording, he continued his prodigious blend of technology and live instrumentation. The tight 10-song set incorporated a variety of sounds and genres much like his 1970s albums.

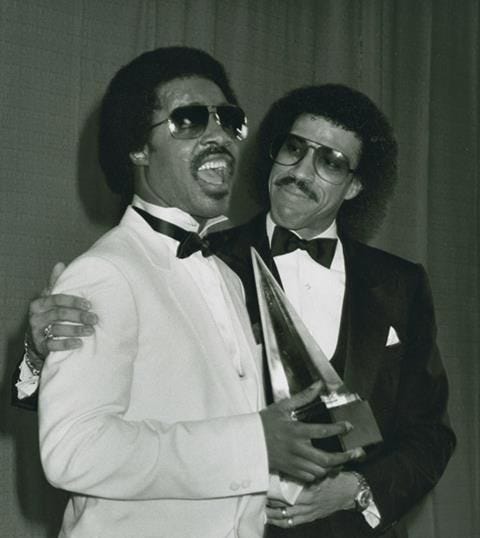

(Stevie Wonder with Lionel Richie at the 1982 American Music Awards. Wonder won the Lifetime Achievement Award. Getty Images)

“Master Blaster (Jammin’),” Wonder’s homage to reggae icon Bob Marley, shot to the top of the Billboard R&B charts and top five on the pop charts. “I Ain’t Gonna Stand For It,” Wonder’s first foray into country music peaked at number 11 on the Billboard Hot 100. “All I Do” and “Lately” became classic fan favorites.

Hotter Than July concluded with what could be considered Wonder’s most enduring composition ever: “Happy Birthday.” Conceived as a tribute to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and outcry for the slain civil rights leader’s birthday to become a national holiday, Black folks everywhere adopted its chorus and coda for every birthday cake candle blow-out to this day.

Wonder’s next release, 1982’s Original Musiquariam I, was a double LP compilation of his biggest hits from his imperial era. He included four brand new songs in the collection, and three of them, “Ribbon in the Sky,” “That Girl” and “Do I Do,” stood head-and-shoulders with Stevie Wonder’s classic canon.

“Ribbon” and “That Girl” followed the DIY tradition of songs like “You Are The Sunshine of My Life” and “Knocks Me Off My Feet,” combining live acoustic instruments with understated synthesizers, while “Do I Do” was a cousin of “Sir Duke,” recruiting a full band of the best and brightest session musicians of the day.

The odd song out on the Musiquarium, “Front Line,” was a prelude to what was to come.

A first-person account of a Vietnam veteran coming home from war to find little to no opportunity and dealing with the aftermath of PTSD, “Front Line” was a contemporary progression of “Living For The City.” However, it had a tinge of preachiness and lacked the righteous indignation of the former. Also, where “Living For The City” had a warmth in its production as Stevie played every instrument, the production of “Front Line” was flat and two-dimensional.

(Getty Images)

In 1984, Wonder dropped The Woman in Red soundtrack. This project found songs completely void of acoustic instruments adjacent to songs with live studio musicians and string sections. The transitions between robotic production up-tempo cuts like the title track and “Don’t Drive Drunk” and organic ballads like “It’s You” and “Weakness” were stark, to say the least.

However, the hit dance single “Love’s Light in Flight” remains a jovial number and contains an electro-funk vibe that’s both time-tested and nostalgic.

Wonder’s final two albums of the decade, 1985’s In Square Circle and 1987’s Characters, had nary a trace of live instruments. Like most acts in the latter part of the decade, the production and engineering watermarked songs like “Part-Time Lover,” “Go Home,” and “Skeletons” to the era.

Compared to 1970s era songs like “I Wish,” and “Boogie On Reggae Woman,” fans feel like much of Wonder’s 1980s songs had a cyborg feel and hindered the heart that went into crafting these songs.

Looking under the surface, however, many of these compositions have the same strength as his prime. Had songs like “With Each Beat of My Heart,” “My Eyes Don’t Cry,” and “Never In Your Sun” been recorded during his classic run, people may have felt differently about these songs.

Another important context to consider when reappraising Wonder’s 1980s catalog is the socio-political climate for Black America in that decade, and Wonder’s response to that musically and personally.

(L-R) Ahmet Ertegun, Paul Simon, Jann Wenner, Stevie Wonder, son, and daughter attending the Fourth Annual Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame Awards on January 18, 1989, at the Waldorf Hotel in New York City, New York. (Photo by Ron Galella/WireImage)

While his actions were byproducts of Black American civil disobedience in the 1960s and 1970s, Wonder’s music reflected a more subdued timbre of the Black experience during the 1980s.

The “Me Decade” was defined by assimilation between Black and white America. African-Americans spent much of the previous decade with the fullest understanding of their place in the country, how the white upper echelon thought of them, and openly embraced their sense of independence and heritage.

Sadly, though, the opportunity to live in the suburbs and have disposable income superseded knowledge of self. If Black folks spent the 1970s being woke, the 1980s found many of them taking sleeping pills because it was easier to believe that things were better, via assimilation than the reality of what the way things were.

Like every movement in the culture of Black America, the songs were the mirror of the mindsets and lifestyle of, what writer Nelson George dubbed, the “post-soul nation.” The tracklist of that soundtrack included music from Lionel Richie, Whitney Houston, Anita Baker, Luther Vandross, Freddie Jackson, Melba Moore, and others. The thematic focus on relationships, good times, and the sleek, polished production and engineering described the aspiration aspect of Black ideals.

George wrote, “Economic clout has granted many black cultural figures an unprecedented level of financial control over their art. Once Berry Gordy was the patron saint of black capitalism, but Godfather Bill Cosby, singer/conglomerate Michael Jackson, TV host/producer Oprah Winfrey, and a legion of others enjoy total product control — though, significantly, not distribution control — over their hunk of culture. That’s an undeniable result of genuine integration.”

Wonder no longer had the time to present a statement in a poetic, nuanced way with coded language. If he was going to get his point across, he needed to make it plain.

Let’s look at a song from each era; 1973’s “He’s Misstra Know-It-All” and 1985’s “It’s Wrong (Apartheid).”

The instrumentation and arrangement of “He’s Misstra Know-It-All” evoke a mid-tempo gospel song, heavy with bass and piano, with a vamp out of exuberant, almost ostentatious drum soloing.The lyrics were addressing former President Richard Nixon amid the Watergate scandal, but his name is never spoken. It describes a sheisty individual who gets where he wants by deception, narcissism, and capitalistic obsession. So many men could fit that mold.

“It’s Wrong (Apartheid)” on the other hand lets you know just from reading the tracklist what you’re going to expect. The production is a slick collection of synthesized poly-rhythms and African chants. The chorus is self-explanatory: “You know Apartheid is wrong/It’s wrong/Like slavery was wrong/Like the Holocaust was wrong/Apartheid is wrong/It’s wrong.”

When you turn on the radio today or watch what songs award shows are honoring in the 21st century, you begin to realize that maybe the simplistic, synth-heavy Stevie Wonder songs from the 1980s weren’t so bad. People who slammed “I Just Called To Say I Love You” may pray that such a song is popular today.

THANK YOU FOR READING! If you enjoyed this piece, please subscribe to my page and share the piece on social media. Thanks again, and stay tuned for more!

Love this overview! This period is when I was actually old enough to discover Stevie on my own. The Luther moment at the beginning of this 12" single always brings me joy, no fail.

https://youtu.be/3bJIUbj_UqY